How Ant Colonies Work: The Hidden Intelligence of Superorganisms

A single ant possesses a brain smaller than a grain of sand with only about 250,000 neurons. Yet when millions work together, they create structures and solve problems that rival human engineering—all without any central command or master plan. This is the paradox of ant colonies: sophisticated intelligence emerging from simple individual behaviors.

The Superorganism Concept

Entomologists refer to ant colonies as "superorganisms"—entities where the colony, not the individual ant, is the unit of natural selection. Just as cells in your body work together to keep you alive, individual ants sacrifice personal interests for colony survival.

This concept was first proposed by William Morton Wheeler in 1911, but modern research has revealed just how literally accurate this analogy is:

- The queen functions like a reproductive system

- Workers act as immune cells, defending against pathogens

- Foragers serve as the digestive system, gathering and processing resources

- Nurses care for the brood like stem cells producing new colony members

Communication Without Words

Ants communicate primarily through chemical signals called pheromones. Each colony produces a unique chemical signature, allowing ants to instantly identify nestmates from intruders.

The Pheromone Trail System

When a forager discovers food, she returns to the nest while depositing a trail pheromone from her abdomen. Other ants detect this chemical trail with their antennae and follow it to the food source. As more ants travel the successful route, they reinforce the trail, creating a positive feedback loop.

This simple system produces remarkably sophisticated behavior:

- Shortest path finding: Multiple trails compete, but the shortest route receives more ant traffic and stronger reinforcement, eventually dominating

- Automatic optimization: If an obstacle appears, ants explore alternatives, and the new shortest path naturally emerges

- Dynamic response: Trail strength decays over time, so depleted food sources are automatically abandoned

Computer scientists have adopted this "ant colony optimization" algorithm to solve complex routing problems in telecommunications and logistics.

The Pheromone Vocabulary

Beyond trail markers, ants use dozens of distinct pheromones for specific purposes:

- Alarm pheromone: Released when threatened, causes nearby ants to become aggressive

- Queen pheromone: Suppresses reproduction in workers and coordinates colony activities

- Recruitment pheromone: Calls for help with large food items or nest defense

- Necrophoric pheromone: Triggers removal of dead ants from the nest

Division of Labor: The Perfect Workforce

Ant colonies exhibit sophisticated division of labor, with individuals specialized for specific tasks. This specialization increases efficiency dramatically—a principle Adam Smith would recognize from human economics.

Age-Based Polyethism

In most ant species, an individual's job changes as she ages (all workers are female):

- Days 1-3: Cell cleaning and egg care

- Days 4-10: Feeding larvae and tending to the queen

- Days 11-20: Nest maintenance and food storage

- Days 21+: Foraging outside the nest

This age-based system makes evolutionary sense: young ants stay safely inside performing low-risk tasks, while older ants take on dangerous foraging duties. If a forager dies, the colony loses an individual near the end of her lifespan rather than a young ant with years of potential productivity ahead.

Morphological Castes

Some species go further, producing workers of different physical sizes specialized for specific roles:

- Minors: Small workers handling delicate tasks like brood care

- Mediae: Medium workers doing general colony work

- Majors (soldiers): Large workers with powerful mandibles for defense and processing tough foods

Leafcutter ants take this to an extreme, with soldiers 200 times heavier than the smallest workers—equivalent to humans ranging from mouse-sized to elephant-sized.

Collective Intelligence and Decision Making

The most remarkable aspect of ant colonies is how they make complex decisions without any leader giving orders. This "swarm intelligence" emerges from simple individual rules interacting in the aggregate.

Nest Site Selection

When a colony needs to relocate, scouts search for suitable nest sites. A fascinating study of Temnothorax albipennis ants revealed their democratic decision-making process:

- Scouts independently search and evaluate potential nest sites

- A scout finding a high-quality site recruits other scouts more vigorously (more trips, faster recruitment)

- As scouts assess the same site, they reach a quorum threshold

- Once enough scouts agree on a site, they begin carrying the entire colony there

Remarkably, this process consistently selects the best available option, even when presented with multiple choices. The colony "decides" through a distributed voting system where the best option naturally accumulates the most support.

Task Allocation

Colonies dynamically allocate workers to tasks based on current needs, without any centralized management. The mechanism relies on simple stimulus-response rules:

- Each ant has a threshold for responding to task-related stimuli

- Ants encounter stimuli (hungry larvae, debris, food sources) randomly

- When stimulus intensity exceeds an ant's threshold, she performs the task

- Task completion reduces stimulus, providing negative feedback

This system automatically balances workforce allocation. If larvae go unfed, hunger signals accumulate, lowering the effective threshold and recruiting more nurses. Once larvae are satisfied, the signal dissipates, and nurses switch to other tasks.

Engineering Marvels

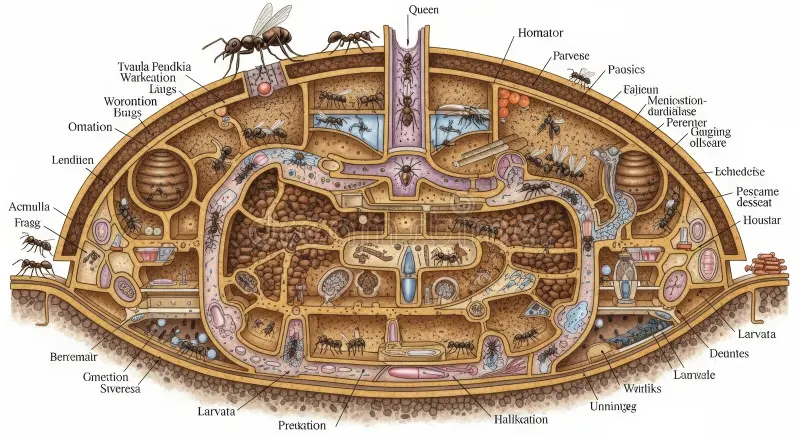

Ant nests are sophisticated structures engineered for specific environmental conditions—all built without blueprints or architects.

Climate Control

Many ant species maintain precise temperature and humidity in their nests:

- Leafcutter ants build ventilation chimneys that create airflow through the nest, controlling CO₂ levels and temperature for their fungus gardens

- Desert ants build nests up to 3 meters deep, accessing cooler, more humid soil layers

- Mound-building ants position their nests to capture solar heat efficiently, opening or closing entrances to regulate temperature

The Living Bridges of Army Ants

Army ants create temporary bridges using their own bodies, allowing the colony to traverse gaps efficiently. Studies show these bridges dynamically optimize their position:

- Ants constantly assess traffic flow across the bridge

- If a shortcut becomes available, bridge ants reposition accordingly

- The bridge finds the optimal tradeoff between travel distance and construction cost

This is pure emergence: no ant understands the overall problem, yet the collective consistently finds near-optimal solutions.

Agriculture and Animal Husbandry

Several ant species practice agriculture, predating human farming by millions of years.

Leafcutter Fungus Farmers

Leafcutter ants don't eat the leaves they harvest. Instead, they cultivate fungus gardens:

- Workers cut leaf fragments and carry them to underground chambers

- Smaller workers chew leaves into pulp

- The pulp fertilizes specific fungus species cultivated only by ants

- The fungus produces specialized nutrient structures the ants eat

This is true agriculture: selective cultivation of crops that depend on the farmer. Leafcutter queens carry fungus samples when founding new colonies, ensuring the next generation inherits the agricultural system.

Aphid Ranching

Many ant species "farm" aphids for honeydew (sugar-rich aphid excretion):

- Ants protect aphids from predators

- They move aphids to better feeding locations

- They stimulate honeydew production by stroking aphids with antennae

- Some species build shelters for their aphid herds

This mutualistic relationship has existed for over 50 million years, demonstrating that ant agriculture rivals human practices in sophistication and duration.

Warfare and Defense

Ant colonies wage sophisticated warfare, employing strategies military tacticians would recognize:

Raiding Strategies

- Scouting: Small reconnaissance groups locate enemy nests

- Overwhelming force: Massive raids with thousands of workers

- Surprise attacks: Coordinated assaults at vulnerable times

- Slave-making: Some species raid other nests, stealing pupae to raise as workers

Chemical Warfare

Ants have evolved diverse chemical weapons:

- Formic acid sprays that can kill or disorient enemies

- Glue-like secretions that immobilize opponents

- Alarm pheromones that coordinate mass attacks

- Repellent chemicals that mark territorial boundaries

The Future of Ant-Inspired Technology

Engineers and computer scientists continue finding applications for ant-inspired algorithms:

- Robotics: Swarm robots using ant-like coordination

- Network optimization: Internet routing inspired by pheromone trails

- Manufacturing: Self-organizing production systems

- Urban planning: Traffic management based on ant trail optimization

As we face increasingly complex challenges requiring coordination without central control—from managing autonomous vehicle fleets to coordinating disaster response—the 150 million year old wisdom of ant colonies offers proven solutions.

These tiny insects, with their grain-of-sand brains, remind us that intelligence isn't about individual capacity but about how individuals work together. In studying ants, we're not just learning about insects—we're discovering fundamental principles of organization, decision-making, and collective intelligence that may hold keys to our own technological and social challenges.